Right to Remix: Appropriation Art in the Digital Age

Monday, April 9, 2012 @ 4:00 PM

New York Law School, April 9, 2012

185 West Broadway, New York, NY 10013

2nd Floor Events Center, 4:00 – 8:00 p.m.

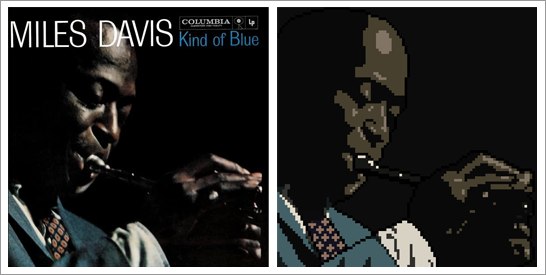

The Copyright Act protects “original expression,” but what is considered “original”? From Girl Talk to Richard Prince, artists are continually borrowing elements of other works to shape their own. Call it “remix,” “mashup,” “appropriation,” or “transformative”—drawing the line between infringement and fair use can be murky!

Join artists, attorneys, and academics for two panel discussions about the ways in which today’s ever-changing technologies have both facilitated the spread of creative work and sparked new debate over the current state of the Copyright Act.

Approximate Timeline:

330 – 400 Sign-In/Registration

400 – 515: Panel I

515 – 530: Break/Cookies/Coffee

530 – 645: Panel II

645 – Onward: Reception/Beer/Wine,etc

*CLE credit will be available.

Panel I: “No Copyright Infringement Intended:” Attribution and the Influence of Digital Content Exchange on Copyright Law

We see it all the time on YouTube: people communicating through shared content without permissions. Although the Copyright Act attempts to balance culture and commerce through exclusive incentive models and fair use defenses, the law just doesn’t seem to be keeping up with the way end users, developers, and content creators operate in the digital sphere. Attributing the original creator can be difficult when there is such a surplus of information on the web and when much of it is built off of preexisting works. What is original anymore? With the influx of innovative technologies comes new opportunities for artists and creators to earn a living, but it is often on the fringes of traditional copyright laws. This panel will gather artists, technologists, lawyers, and students to discuss how the law operates within these new business models, where the confusion sets in, and what needs to be done moving forward.

Panelists:

- David Carroll, Director, Design and Technology (M.F.A.) graduate program, School of Art, Media and Technology, Parsons The New School for Design

- Kirby Ferguson, writer and filmmaker (Everything Is a Remix)

- Paul Miller a.k.a. DJ Spooky, That Subliminal Kid, electronic and experimental hip hop artist

- John Brit Payne, intellectual property attorney, Foley & Lardner LLP

- Maria Popova, cultural commentator and founder, Brain Pickings

Panel II: What is the Message? Transformative Commenting and the Chilling Effects of Judges as Art Critics

Before Cariou v. Prince, most copyright infringement claims associated with appropriated works were settled out of the court. However, after Judge Batts’ ruling in favor of the plaintiff, the debate in the art community over copyright law became heated. The Copyright Act allows a fair use defense for certain transformative works; however, how do the courts decide what constitutes “transformative?” Many judges are looking to the artist to comment on their own works to validate their transformative value; however, this often runs counter to the creative methods and ideas behind the artwork. This begs several questions. What gives a work its meaning? The artist’s intention, the viewer, or the context of the work itself? How should a judge make these decisions about art? Should the “transformative” requirement be taken out of the picture entirely? Is market effect the real issue here when it comes to the art world? This panel will bring together artists, lawyers, professionals, and students to discuss the subjective nature of fair use determinations and their effects on the art community.

Panelists:

- Michelle Bogre, Associate Professor, School of Art, Media, and Technology, Parsons The New School for Design

- Daniel Brooks, Partner, Schnader Harrison Segal & Lewis LLP (attorney for plaintiff in Cariou v. Prince)

- Paddy Johnson, founding editor, Art Fag City

- David Ross, Art Practice Department Chair, School of Visual Arts

- Sergio Sarmiento, Artist and Associate Director for Volunteer Lawyers for the Arts in New York City

Please RSVP to [email protected].