Website privacy policies can be complicated and confusing. The lack of a standard in both presentation and terminology makes it difficult for the average consumer to understand a website’s privacy policy, an understanding which is necessary to make an informed choice whether to use a particular website’s services. In A “Nutrition Label” for Privacy, Patrick Kelly, Joanna Bresee, Lorrie Cranor and Robert Reeder present a way to display online privacy policies in a consumer friendly manner in the spirit of the ubiquitous nutrition label.

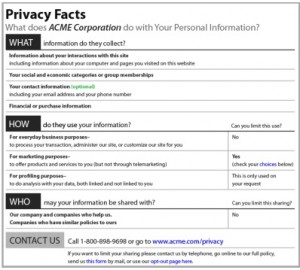

The authors’ proposed label, the “Privacy Nutrition Label”, uses a grid to display the privacy policy with the rows displaying the types of information collected and the columns showing how the information might be used and to whom the information might be shared. A privacy symbol is displayed in the intersection of each row and column representing the severity of the privacy practice. The label consists of ten rows of information collected with five ways of using the information and two outlets for sharing the information totaling seventy cells, each displaying a privacy symbol. This is a large amount of information to sort through no matter how cleanly organized. Multiply this by every website that you might interact and do business with and it only gets worse. I personally prefer an earlier iteration of the authors’ label, the “Simplified Label”, which displays the privacy policy in a series of Yes/No statements. Although it lacks the detail of the grid and may exaggerate the permissiveness of the policy because of grouping categories together for simplicity, it is easy to understand and quick to read. A possible compromise might be to allow the Yes/No statement to be expanded into a more detailed breakdown if the user feels the policy is too permissive and wants to know more about it.

|

|

The authors’ project is a great start to simplify privacy policies but should be expanded to address two more concerns, the permanency of the information collected and mutability of the privacy policy. The first issue is simply how long the company will store the information collected about you. If I purchase a book from an online seller, how long will the company keep my credit card information? How long will it keep my address and phone number? This can be addressed simply by supplying a column in the “Privacy Nutrition Label” to display the length of time data is kept or a time range in the “Simplified Label” that can be expanded for more detail if desired. The second issue addresses what happens when the company changes its privacy policy. Will the company notify the consumers whose information the company has already collected when it makes a change to the privacy policy? How will the consumers know the policy has changed otherwise? What happens to the information already collected? Will that information now be subject to the new terms? A Big Mac purchased under the “terms” of one nutrition label is not going to be retroactively affected if McDonalds changes the recipe at a later date whereas data residing on Facebook might. The solution to this is a mechanism to show how and when a policy has changed.

The has developed to address this very issue. TOSBack monitors the privacy policies of various websites and publishes the changes made to those policies. Something like this would be very helpful if incorporated into the privacy label itself to allow the consumer to see a policy change when revisiting a particular website. This of course would not help a consumer who uses a website for a one-time purchase and never returns but it is a start.

A larger problem with the privacy label project in general is with its adoption. A project such as this is only as useful as the size of its implemented base. Moreover, companies must agree on how to implement it. It would defeat the purpose to have different companies presenting their privacy labels differently, such as using different colors or symbols for privacy statuses. Such inconsistencies would only further complicate and confuse the consumer. Maybe this is a case where government regulation would be helpful. A regulatory agency such as the Federal Trade Commission could ensure that the use of such labels were widespread as well as preventing the proliferation of dissimilar privacy labels.

Overall the authors’ project is a noble one and one that I think whose time has come. Consumers deserve to understand the policies surrounding the data collected about them without having to struggle through pages and pages and legalese. The keys to the project’s success are adoption and standardization, without which the project is simply a great idea.